I toured a Southern plantation a few years ago, and while I found it fascinating, it was also disturbing. The focus was on the plantation house and its elegant décor, plantation family history, and how sugar cane was harvested and cooked down to crystals. You might forget altogether that the place was run on the backs of slaves, until you come to a row of shacks, and the guide briefly describes life in the plantation’s slave quarters. At that point in my tour, people got very quiet. So much goes unsaid.

John Cummings, a wealthy white New Orleans lawyer, bought the Whitney Plantation in 1999 as one of many real estate investments. He had no specific intentions for the property at the time, but when he was going through all the historic papers of the plantation, he saw a list of slaves and their estimated values. “There was one female slave named Mary,” he told me when we conversed, “She was worth three times what other females were valued. Next to her name, it said, ‘good breeder.’ She was bred like a horse to produce more slaves.” That’s when it hit him, the blood and sorrow he was standing on. And the more he learned, the more aggrieved he became.

For the next 15 years, Cummings immersed himself into transforming the Whitney Plantation into a slavery memorial and museum. In 2000, he began collaborating with Senegalese scholar Ibrahima Seck, who took on the role of museum historian, unearthing names of slaves who had worked on the plantation before emancipation. The two have worked together for last 15 years, and Cummings has poured 8 million dollars of his own money into what he considers to be the project of his lifetime.

The Whitney Plantation opened its doors on Dec. 7, 2014, and as the first plantation museum dedicated to honoring slaves, it’s been getting a lot of attention. (Click here for a New York Times article on it.) I heard about the place from my sister, who went there a few months ago. Kate and I went on our last day in New Orleans, along with my nephew’s girlfriend, Casey.

Normally busy enough to require tour reservations, it was pretty quiet on the last day of the holiday weekend. There were only about 10 in our group. Our guide, De’Laun, first took us to a pretty, white church. The Antioch Baptist church was founded by freed slaves in 1867, the first black church in Louisiana. Cummings found it in a neighboring parish and had it moved and renovated. Not only is it in beautiful shape now, but it is filled with two dozen haunting statues of slave children.

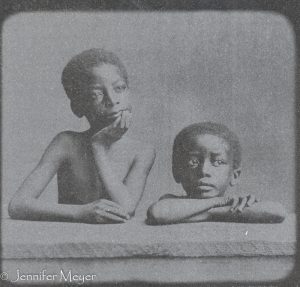

The statues were commissioned by Cummings from artist Woodrow Nash. He created 63 of them, which are dispersed throughout the grounds. In the church, we watched a short film about the Federal Writers Project, which was established by Franklin Roosevelt as part of the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act. Thousands of writers were employed to collect and archive oral histories of freed slaves. Each of the statues in the church around us depicted the youthful image of one of the Louisiana slaves interviewed. We were encouraged to walk around the church and study these images. They were so lifelike, in natural casual poses, yet with hollowed out eyes that had a chilling effect. It was impossible not to think about life on this plantation for a young slave, and to feel moved.

From the church, De’Laun took us to an outdoor memorial, the “Wall of Honor.” Modeled after the Vietnam Veteran’s Memorial Wall in D.C., this memorial includes granite walls engraved with the names of 107,000 Louisiana slaves, including the 354 slaves who worked on the Whitney plantation. It also includes the tally of Whitney slaves for auction, listing each slave by name, age, skills, and value. Quotes from slave oral histories are interspersed.

You could easily spend an hour here, but we moved on to the next memorial, one built to honor the 2,200 enslaved babies and young children who died in this parish in the 40 years before emancipation. In the center of granite walls engraved with names, photos, and quotes is a lifesize sculpture of a black angel holding a lifeless baby.

There’s no gliding through this tour. Hot as it was that day, my arms had goosebumps the whole time I was there, and everyone with us was somber, even though De’Laun’s demeanor was upbeat and candid. We were shown one of seven slave cabins on the property, and walked by an iron holding cell used to keep slaves, sometime for days, before they were auctioned off.

We walked by a renovated blacksmith shop (where Jamie Fox was branded in “Django Unchained”), and looked in on the state’s only separate “kitchen house” still standing. At last, we came to the plantation house, which in this tour, unlike other plantation tours, was almost an afterthought. It was not especially grand, and the furnishings were sparse. The walls and ceilings were elaborately painted however, and had been painstakingly restored over the last few years.

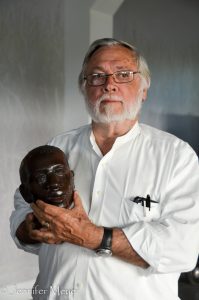

In the gift shop after the tour, I saw John Cummings, with whom I’d briefly chatted when we first arrived. I gave him my impressions and asked him questions about the museum’s history. Seeing my interest, he took us into a back room to show us a new project he was working on. He picked up one of several porcelain heads. In January 1811, 125 local slaves revolted and, after killing two plantation owners, went on a two-day march along River Road to New Orleans, gathering forces and burning plantations along the way. They were met by militias in New Orleans, and 95 slaves were killed. To warn others against following suit, the bodies of killed slaves were decapitated, and their heads placed on spikes along River Road and in Jackson Square in New Orleans. Cummings’ latest memorial will be a gruesome and jolting display of 60 slave heads, mounted on spikes that sway in the wind.

What a remarkable and moving experience to have! I’m adding the Whitney Plantation and Slave Museum to my “must see” list. Very powerful accounting of your time there. Thanks for posting this one.

Thanks, Evelyn. I can’t believe that there hasn’t been a museum like this before. It is so important, and it’s still growing.